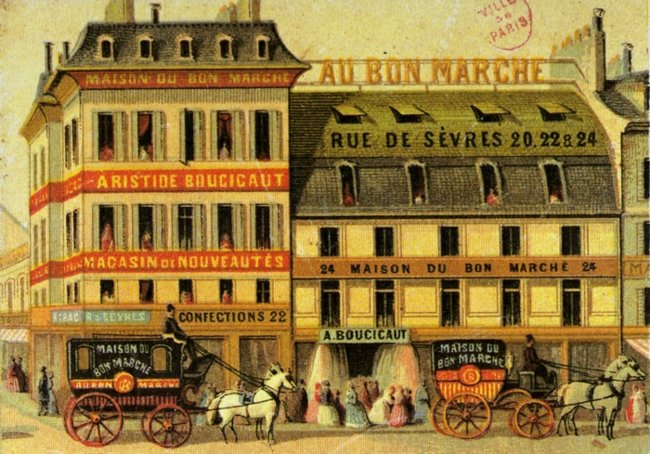

Michael B. Miller, The Bon Marché: Bourgeois Culture and the Department Store, 1869-1920

Buying and Selling Before the Department Store

... department stores, in France as elsewhere, did not spring up overnight. All the great emporia of the prewar era -- the Bon Marche, the Louvre, the Printemps, and others -- had either modest or intermediate origins, all passed through a magasin de nouveautes phase, and all were predicated upon new commercial practices and upon new commercial frames of mind that had developed in the decades immediately preceding their founding.

-- had either modest or intermediate origins, all passed through a magasin de nouveautes phase, and all were predicated upon new commercial practices and upon new commercial frames of mind that had developed in the decades immediately preceding their founding.

To appreciate the degree to which the magasins de nouveautes departed from traditional merchandising practices in France, it is necessary to recall the conditions of retailing bequeathed by the ancien regime and still predominant at the time of the creation of the July Monarchy. Before the Revolution, most retailing in France was governed by a guild system concerned primarily with maintaining established levels of craftsmanship and with assuring that no merchant or small producer (and most often these were one and the same) encroached on the trade of its neighbor. The guilds regulated and limited entry into the various trades. They insisted that each seller be confined to a single speciality and to a single shop; they set standards of work; and they set conditions for procuring supplies. At times they set a minimum selling price to prevent “unfair” competition. Advertising was effectively restricted to street signs and street cries, listings in almanacs, and, apparently more exceptional than the rule, almanacs by individual proprietors that might also serve as a store prospectus. Thus little leeway was left to entrepreneurial innovation.

This picture is, to some extent, an incomplete one. There were certain "privileged places" of commerce in each major town that were outside the guilds's jurisdiction, as were the colporteurs or peddlers that thronged the city streets. There were also the great fairs and the merciers, the one group of merchants who were permitted to sell all varieties of merchandise (although they were prohibited from all forms of manufacture). Yet none of these represented much of a break with the prevailing traditions of the period. The "privileged places" tended to establish their own guild-like regulations, while colporteurs, who might engage in more competitive trading, were by their very nature anything but the vanguard of a commercial revolution. Fairs were but seasonal events among individual sellers, and in no way may these be seen as predecessors to department stores. As for the merciers, their shops were at best early models of general stores, while their merchandising habits, covered by guild restrictions, remained the same as those of their less diverse colleagues.

This does not mean that we should discount all possibility of changing attitudes beneath a more visible guild screen. The constant accusations and litigations within the guild communities point to the restlessness of a number of their members. Nor should we doubt that the advances in window display and store decor that were common in London in the eighteenth century were unknown to the Parisians. But if we truly wish to cite examples of a shift from the governing norms of the times' we must wait until the end of the eighteenth century, when new stores calling themselves magasins appeared on the Parisian scene. One of these, the Petit Dunkerque, is known to have sold at fixed prices rather than abiding by the ritual of bargaining over each item. Characteristic of the period, however, these stories did not make much immediate headway, nor did they differ significantly from the merciers out of which they had evolved.

It might be expected that some greater change would have occurred with the suppression of the guilds [during the French revolution], but few shopkeepers were prepared to abandon either the traditions or the mentality of the past. Again there were exceptions, enterprising merchants like Balzac's perfumer, Cesar Birotteau, who did not shrink from pursuing greater sales or from employing ambitious publicity schemes to achieve these ends. Yet it was in the proprietor of the Maison du Chatquipelote that retailers during the opening decades of the new century would undoubtedly have recognized their portrait, and to glimpse behind the centuries-old facades that housed the boutiques of Paris in these years would be to find a way of business that differed little from its pre-Revolutionary predecessors. If stripped of its legal sanctions, the guiding principle for the community of shopkeepers remained the right of each honorable merchant to a set share of the trade, and there was no need of a French Malthus to justify in prose what all shopkeepers already were certain of -- that any increase in sales on the part of one of their number would result in a corresponding decrease for the others. Consequently, the boutiquiers [small shop keepers] persisted in their confinement to traditional specialties and bitterly resented any move toward merchandise diversification by competitors.

It might be expected that some greater change would have occurred with the suppression of the guilds [during the French revolution], but few shopkeepers were prepared to abandon either the traditions or the mentality of the past. Again there were exceptions, enterprising merchants like Balzac's perfumer, Cesar Birotteau, who did not shrink from pursuing greater sales or from employing ambitious publicity schemes to achieve these ends. Yet it was in the proprietor of the Maison du Chatquipelote that retailers during the opening decades of the new century would undoubtedly have recognized their portrait, and to glimpse behind the centuries-old facades that housed the boutiques of Paris in these years would be to find a way of business that differed little from its pre-Revolutionary predecessors. If stripped of its legal sanctions, the guiding principle for the community of shopkeepers remained the right of each honorable merchant to a set share of the trade, and there was no need of a French Malthus to justify in prose what all shopkeepers already were certain of -- that any increase in sales on the part of one of their number would result in a corresponding decrease for the others. Consequently, the boutiquiers [small shop keepers] persisted in their confinement to traditional specialties and bitterly resented any move toward merchandise diversification by competitors.

Malthusianism of this sort equally stunted the development of an aggressive sales policy. Advertising, aside from traditionally acceptable methods, was rejected almost out of hand, and apparently the idea that consumption could be encouraged through price or service innovations never occurred to these merchants. If it did, it too was evidently dismissed as beyond the pale of respectable practice. Hence turnover was simply not a marketing concept, and profits were sought strictly through the medium of high prices on individual sales. Nor was any attempt made to turn buying into a pleasant or convenient experience. The idea of "shopping" was, for all practical purposes, non-existent, as entry into a shop entailed an obligation to make a purchase. Returns or even exchanges were unheard of. Indeed caveat emptor was the ruling doctrine of the day. Consumers were offered neither fixed nor marked prices to guide their way, and the common practice was to sell only after a long period of bargaining -- and probably haggling-over the price. 5 Undoubtedly some shopkeepers were scrupulous, but the image handed down to us is that many others were not, and most likely one entered a shop prepared for deception rather than service.

Why, with this lack of merchandising finesse, the shopkeepers of Paris should have nevertheless embellished their boutiques with lavish trappings is uncertain. Perhaps it was simply a matter of personal pride. Perhaps as well it was simply another example of their rudimentary understanding of marketing, since most shopkeepers -- for the most part dependent upon credit sales and hence frequently lacking sufficient working capital -- could ill afford to squander their initial investment on outlays that accorded so little with their merchandising philosophy. 6

Au Bon Marché before it became a modern department store